Health

Scientists Find Norovirus And Other Gut Viruses Can Spread Through Saliva

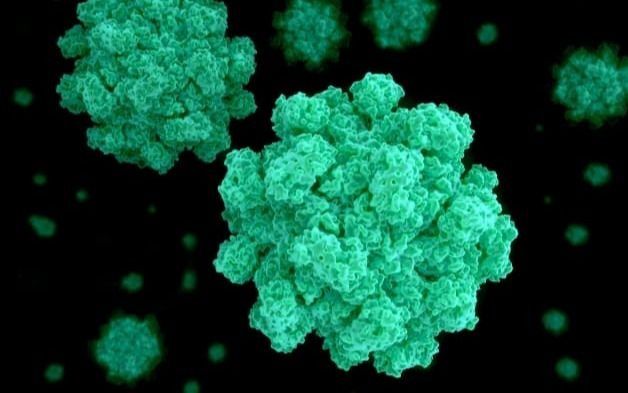

Scientists have made the startling discovery that a class of viruses that are known to cause severe diarrheal diseases, including the one that is famous for widespread outbreaks on cruise ships, can grow in the salivary glands of mice and spread through their saliva. The findings reveal that there is a new mode of transmission for these prevalent viruses, which affect billions of people every year throughout the world and have the potential to cause fatalities.

Since these so-called enteric viruses are thought to be transmitted by saliva, it implies that coughing, talking, sneezing, sharing food and utensils, and even kissing, may also be capable of spreading the viruses. The new findings have not yet been confirmed in research involving actual people. The new findings have not yet been confirmed in research involving actual people.

The new findings have not yet been confirmed in research involving actual people.

These findings, which have been published in the journal Nature, may one day lead to improved methods for diagnosing, preventing, and treating diseases caused by these viruses, which could ultimately save lives. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), which is a part of the National Institutes of Health, was in charge of the study.

Researchers have known for some time that the most common way for enteric viruses, such as noroviruses and rotaviruses, to be passed from person to person is through consuming food or drinks contaminated with faecal matter that contains these viruses. Enteric viruses were thought to bypass the salivary gland and target the intestines, leaving the body through faeces. Although some scientists have suspected another method of transmission, this theory has primarily remained untested until now.

Now, researchers will need to confirm whether or not the transmission of enteric viruses through saliva is possible in humans. According to the researchers, if they find that it is, they may also discover that this route of transmission is even more common than the conventional route. They said that a finding such as that could help explain why the large number of enteric virus infections that occur each year around the world does not sufficiently account for faecal contamination as the only transmission route.

“This is completely new territory because these viruses were thought to only grow in the intestines,” said senior author Nihal Altan-Bonnet, Ph.D., chief of the Laboratory of Host-Pathogen Dynamics at the NHLBI.

“Salivary transmission of enteric viruses is another layer of transmission we didn’t know about. It is an entirely new way of thinking about how these viruses can transmit, how they can be diagnosed, and, most importantly, how their spread might be mitigated.”

The discovery, according to Altan-Bonnet, who has spent years researching enteric viruses, was entirely coincidental. Her team had been conducting experiments with enteric viruses in infant mice, which are the animal models of choice for studying these infections due to the immaturity of their digestive and immune systems, which makes them susceptible to infections.

For the current study, the researchers fed a group of newborn mice that were less than 10 days old with either norovirus or rotavirus. The mouse pups were then returned to cages and allowed to suckle their mothers, who were initially virus-free. After just a day, one of Altan-Bonnet’s team members, NHLBI researcher and study co-author Sourish Ghosh, Ph.D., noticed something unusual. The mouse pups showed a surge in IgA antibodies — important disease-fighting components — in their guts. This was surprising considering that the immune systems of the mouse pups were immature and not expected to make their own antibodies at this stage.

Ghosh also noticed other unusual things: The viruses were replicating in the mothers’ breast tissue (milk duct cells) at high levels. When Ghosh collected milk from the breasts of the mouse mothers, he found that the timing and levels of the IgA surge in the mothers’ milk mirrored the timing and levels of the IgA surge in the guts of their pups. It seemed the infection in the mothers’ breasts had boosted the production of virus-fighting IgA antibodies in their breast milk, which ultimately helped clear the infection in their pups, the researchers said.

The researchers wanted to know how the viruses got into the breast tissue of the mothers in the first place, so they conducted additional experiments. They discovered that the mouse pups had not transmitted the viruses to their mothers through the conventional route, which is for the mouse pups to leave their contaminated faeces in a shared living space for their mothers to ingest. That’s when the researchers decided to see whether the viruses in the mothers’ breast tissue might have come from the saliva of the infected pups and somehow spread during breastfeeding.

To test the theory, Ghosh collected saliva samples and salivary glands from the mouse pups and found that the salivary glands were replicating these viruses at very high levels and shedding the viruses into the saliva in large amounts. Additional experiments quickly confirmed the salivary theory: Suckling had caused both mother-to-pup and pup-to-mother viral transmission.